“Almost all good writing starts with terrible first drafts” is one of many insights into the art of writing from author Ann Lamott. As a C- high school English student, former high school English teacher, and successful doctoral student, I’ve written and read my fair share of terrible first drafts. Because of these experiences I think I’ve earned the right to have my own insights about writing, how to teach it, and more importantly, how to create opportunities for young people to grow into confident writers.

For those of you who know me, you’ve probably heard my story about being an avid reader, writer, and published poet, until September of my freshman year of high school when a teacher shared some pointed feedback in crisp red pen on an unfortunately terrible essay about Gilgamesh. After that moment I quit English, abandoned books, and stopped writing. Spoiler alert: I found my way back. (All that happened in between is a story for another time.)

Since the trauma of the red pen I’ve grown into a (mostly) confident writer. I’ve also had the privilege of learning from all of the mistakes my students and I made together over my ten years in the English classroom and three years it took me to write my dissertation. The most valuable takeaway for me was the power of writing to learn over learning to write.

One aspect of the Village School learning design that impressed me the most when my family first joined the school five years ago was the volume of writing to learn that was required. Teachers, and especially high school teachers, are cautious about the volume of writing assignments because the more writing, the more pages to grade with that infamous red pen. Most classrooms are places where writing is expected to be formulaic (easier to grade), perfect (easier to grade), and without individual voice (easier to grade).

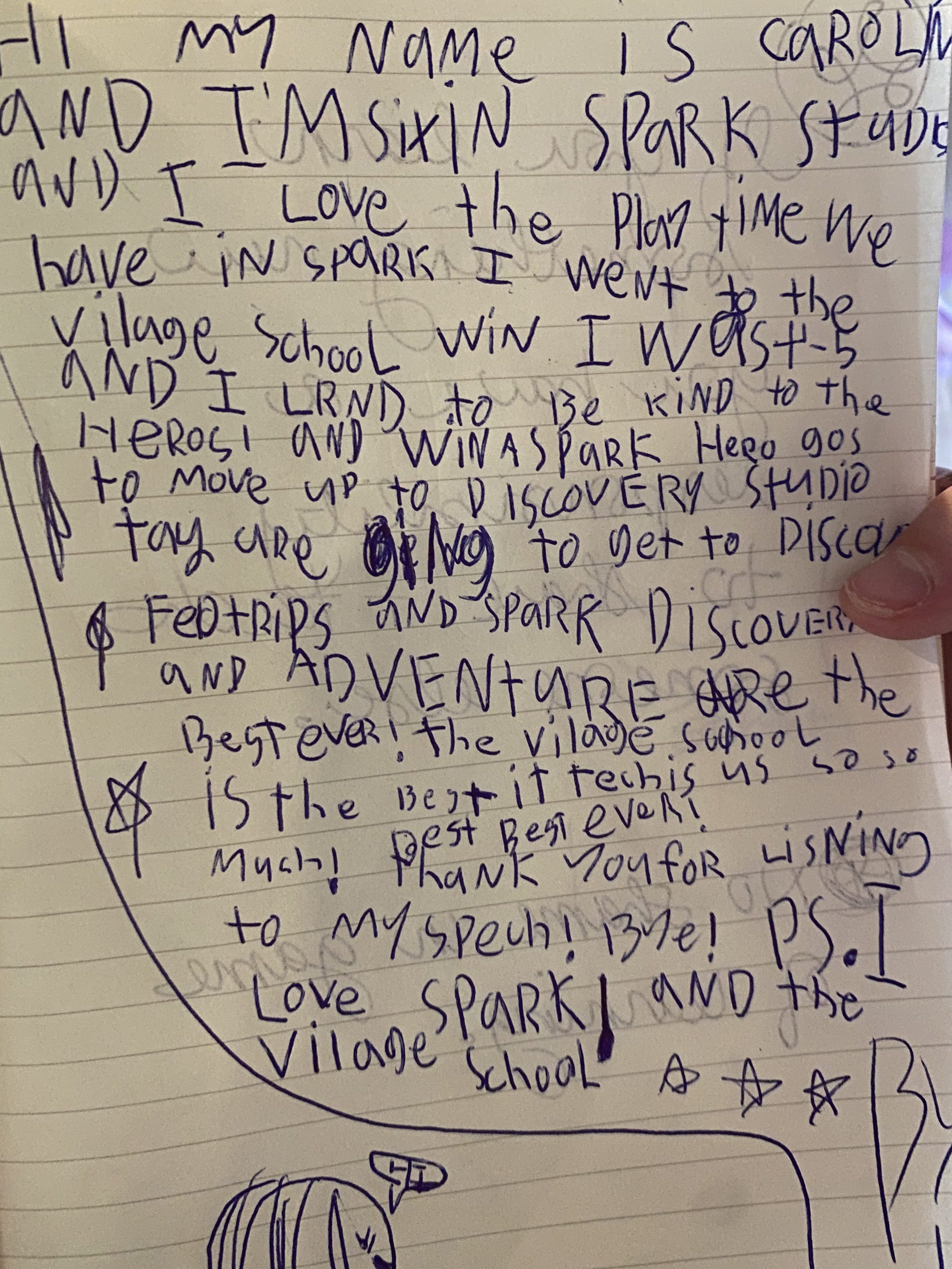

Writing to learn is different from learning to write, as the focus positions writing as a powerful tool for thinking, exploring ideas, and developing intellectual identity. Additionally, writing itself is one of the most significant acts a person can make in terms of deep learning. The primary goal at TVS is that we foster an environment where young people develop their writer’s voice and belief in their ability as a writer. We expect to see lots of mistakes in those terrible first drafts and even in some final submissions. We refrain from the red pen because we’re choosing to focus on long term growth over short term perfection.

The quickest way to squash a developing writers’ confidence is to take a red pen to a piece of writing to correct lower order concerns like grammar or spelling mistakes. If you don’t believe this, my ninth grade self will tell you how it feels to have an adult point out all that is “wrong” with your paper and so will the research. The most impactful feedback anyone can provide to another writer is feedback on the ideas present in the writing, not the technical aspects. These are known as higher order concerns, and what college writing centers focus on and so do TVS guides. Feedback should cause thinking, not more work.

I know this begs the question – and I know what some of you skeptics might be thinking. Trust me, my mother asks the same questions out loud (not in her head). “These kids need to learn capitalization!” “But, what about commas?” “Please, diagram some sentences!”I hear her, and I hear you. Parents often have the same questions and are skeptical about the type of feedback their learners receive on writing specifically – because they, like many adults, are looking through the lens of that infamous red pen. A missing period or misused comma are an easy correction that might seem harmless, however this type of feedback misses the mark, pun intended. Sometimes these questions emerge after we send home TVS elementary schoolers standardized test scores that show a deficit in these technical aspects of writing (that are a lot easier to ‘measure’ than creative ideas and a compelling thesis). However, those same test scores also report that by the time learners get to 8th grade, they’ve figured it out without any formal grammar instruction. (Please tell my mother!)

A writing to learn approach is not an abandonment of these conventions, it’s about a trust that these aspects of a piece of writing will become important to the learners over time. It’s a testament to the constructivist belief that The Village School is built upon, as well as our intentional design for deep, purpose driven learning.

Recently a parent stopped me to share about their fifth graders’ middle school visit day experience. They specifically wanted to share with me how proud their child was about completing the Civilizations writing assignment – a rigorous task that most learners new to middle school find quite challenging. I smiled as they shared their critique of their learner’s essay. In their own words: “it was terrible.” I asked the next question about the parent’s response with my fingers crossed. And as they answered with a knowing smile and reported that through gritted teeth they told their learner how great it was. (High-five, TVS parent!) Terrible first drafts are exactly what we are going for, more often than not.

So, the next time you show up to an Exhibition or are reviewing a young person’s writing, ask them questions about the ideas in their writing instead of the technical aspects like the format or the font (unless it’s Comic Sans.) And, fine, if you just can’t help yourself, we give you permission to correct just one (of the most likely many) grammar mistakes. As long as you promise to remember: they are writing to learn.