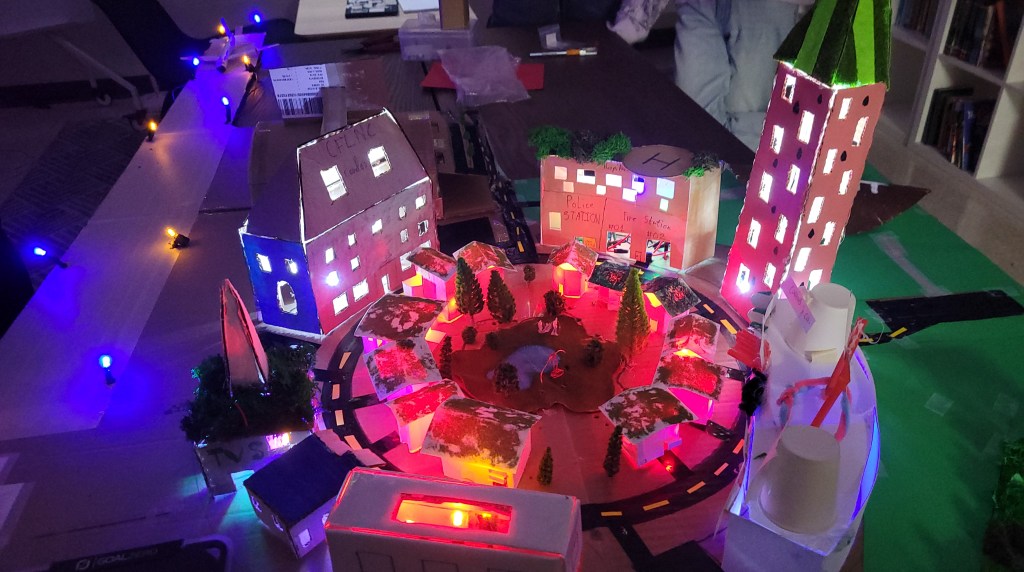

Learning at The Village School is an active experience that connects young people to the community in which they live and beyond. Since Session 1 of this school year learners across our three of our studios have connected with our local community by welcoming experts onto our campus to share their experiences and by embarking on over a dozen field trips and counting.

Connecting with community experts

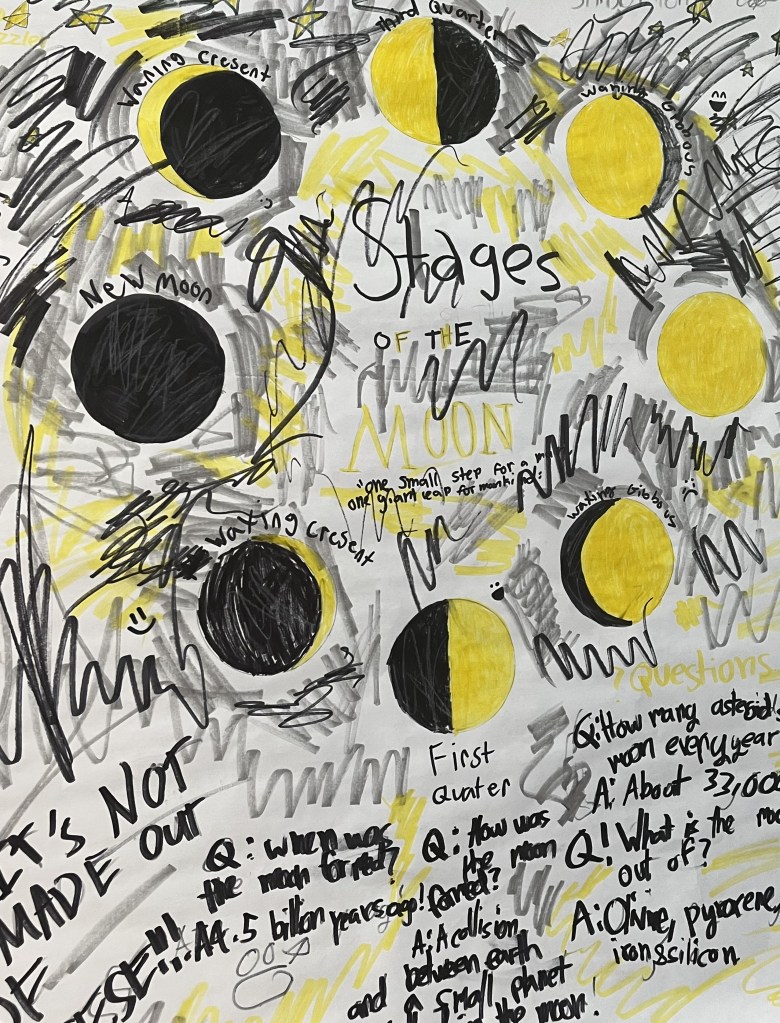

Learners have heard from community experts including a reporter from Arlington Now, US Park Ranger Jen from the National Mall, a Peace Ambassador, an Arlington County City Planner, Professional Lobbyists for the National Guard, Yoga Instructors and personal trainers, the Arlington County Park Manager, and a biologist from The Stark Lab. While career-day might be a once a year event in the typical school, the inclusion of subject matter experts into the learning design of each six-week session is a unique and intentional aspect of the TVS model. Research focused on the importance of representation reveals the importance of these experiences for all young people – as the saying goes, they must see themselves before they can believe in themselves.

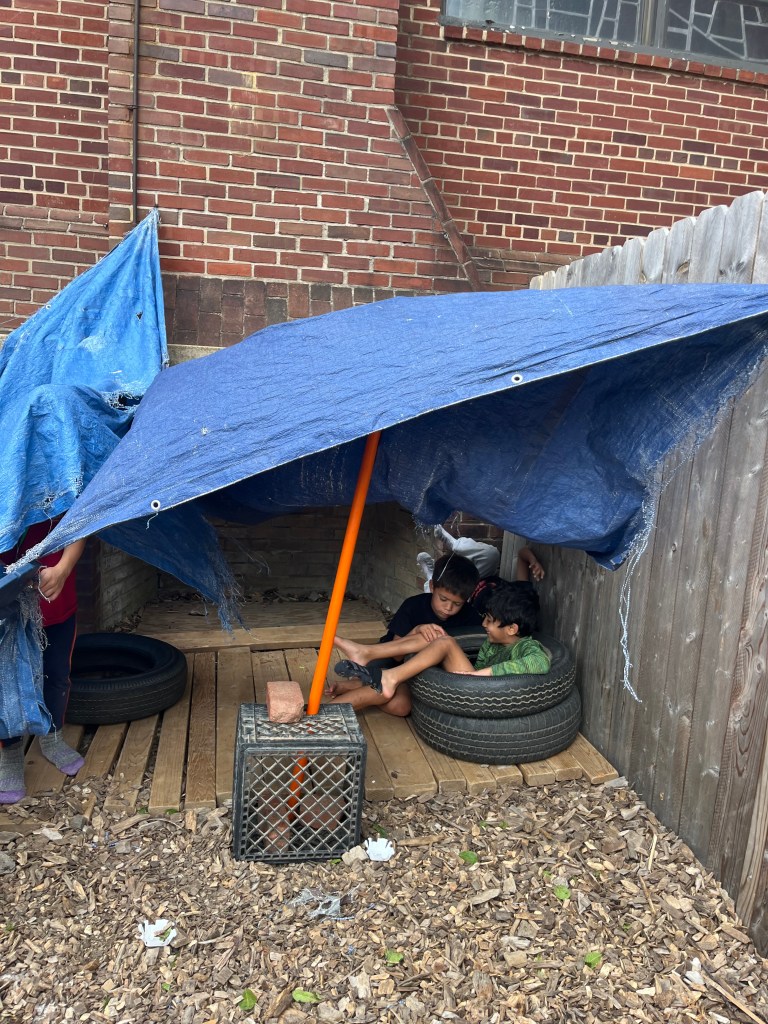

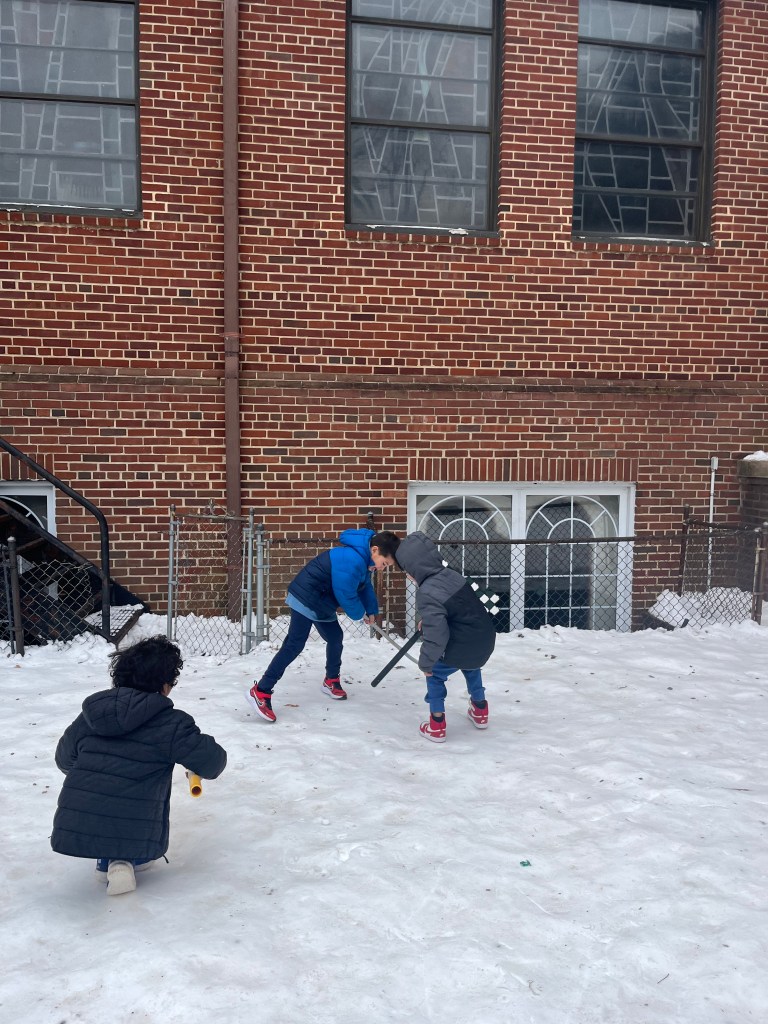

The Community as Classroom

Learners have also ventured out into the community for a total of 12 (and counting!) field trips to the Senate Offices on Capitol Hill, the National Museum of American Indian, the Hirshhorn, the Holocaust Museum, the Washington Monument, the Air & Space Museum, and CBS morning news studios, where they were featured on the local news! Each of these field trips have required the use of public transportation – part of the field trip experience that we believe is just as important as the final destination.

Middle school learners have also ventured out to our community trails and hiked two of three planned hikes so far this year. In addition to the organized field trips learners travel off-campus and into the community each week to visit the park, which we have officially adopted, and the library. Similar to the once-a-year Career Day, learners in a typical school might have a once-a-year opportunity to attend a field trip with their class. Our school size, flexible schedule, and access to public transportation make taking a field trip to explore our local community easy in comparison.

Thanks to The Village Fund we’ve extended our community to reach beyond the Washington DC Metro stops. Elementary learners took the very first TVS charter bus trip to the Baltimore Aquarium to observe oceanic biomimic inspiration. Middle schoolers kicked off their study of physics with a trip to iFly and will celebrate their year-long focus with a bus trip to Hershey Park for their Physics Day.

Community driven learning is one of the three main pillars of the The Village School learner experience, and as you can see, we are loyal to our design. Community engagement is an important part of the learners’ experience that starts with involvement in the studio community and ends with middle schoolers’ involvement in apprenticeships that transcend the TVS campus. The experience-based Apprenticeship program places trust in a young person to learn about themselves, explore interests, and develop passions through active participation in the world of work. A Village School graduate will leave our community with an expansive web of connections that reflects a minimum of 3 Apprenticeship experiences, and a sense of self and community support that will far exceed their peers.

Our goal is that TVS learners feel like a valued member of their community and most importantly – like they have the power to change their community for the better, because we know they can, and they will.