As a guide who recently graduated college and moved states away from my family, I’ve been grappling with some personal challenges, which made last week particularly tough.

However, amidst those difficult times, I also experienced an overwhelming amount of love and support when I came into work each day, not just from my fellow guides, but from every learner in the Adventure studio.

On Monday, some of my coworkers noticed I was upset and surprised me with lunch and snacks, bringing me to tears. The learners noticed that I wasn’t myself, and offered support: “Are you okay?”, “What happened?”, and “What can I do to help you?” Feeling the overwhelming love and support, I went home that day thinking, “Wow, I can feel the support of the community” and “I am so extremely grateful to be a part of the culture we are building.”

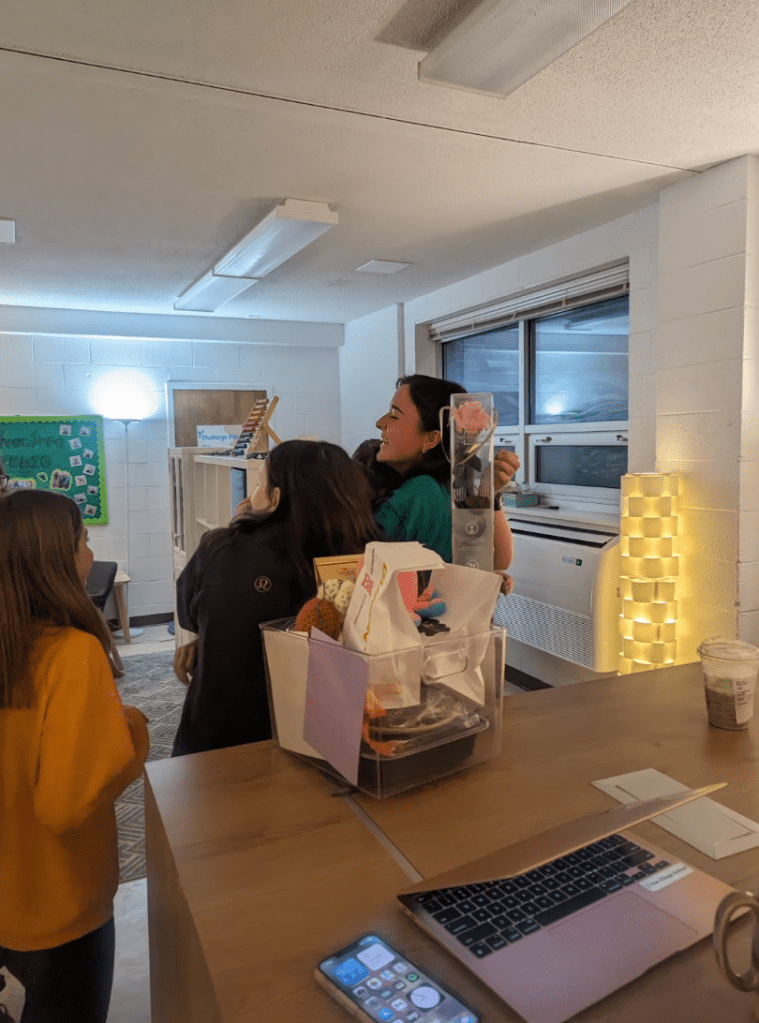

The next morning a group of Adventure learners approached me with another form of support – a bin full of goodies, from homemade cookies and brownies to a stuffed animal they made. Included was a card that read “I just want you to know we are here for you. Whether you need to talk to someone, you need someone to make you laugh, we are here!”

At that moment, I thought to myself, “I can see the model working. I can really see how this school differs from every school I have been to and any place that I had worked before this.” I was blown away by the compassion and empathy the learners had.

When I shared this story with my friends and family, they responded “your middle schoolers did what??” followed by, “Oh Gosh, that would’ve never happened at the schools I went to.”

These are not the only stories of empathy at The Village School, but just one of many.

I’ve also witnessed this sense of belonging and support many times since the beginning of the year. Recently the middle schoolers went on a three day camping trip. After a long day of hiking in the rain, the girls settled into their tent and realized that one of the learners’ sleeping bag was completely soaked through, and she was freezing. Without a thought, another learner rearranged their own set-up to make more room and dry space. What strikes me as so special about this moment and the other moments like it, is that the learners do the next right thing without asking for help, assistance, or guidance. They do the next right thing because it’s the right thing to do and they really do care about each other.

These stories of empathy also include moments during work periods when learners notice a friend struggling to meet their goals. Just this week, a learner completed their pre-algebra badge and the entire studio erupted in cheers, acknowledging all the hard work that had led him to that point. This is evidence of a culture of care and collaboration, which is in contrast to the culture of competition that is the status quo in many schools.

At The Village School we care about who the learners are, rather than what they know and these stories are just some examples of how a culture of belonging and support are enacted in our studios every day. We lift eachother up when we are down. We help each other through the lows, and cheer for each other through the high.

Our learners have the opportunity to cultivate close relationships with their guides and peers. Unlike traditional schools, where students frequently switch classes, here they work closely with guides across subjects. As guides, we strive to understand each learner individually, including their progress, passions, goals, needs, strengths, and learning style. This understanding extends beyond academics, allowing us to nurture a community that is empathetic, loving, and kind. We genuinely care about each learner, demonstrating to them that they belong and are valued in our community.