Just this week I was reminded about a moment of failure that I endured as a TVS guide. Three years ago I was brand new to the TVS team, leading the middle school studio – which then was made up of mostly sixth graders. As an educator I had spent the past fifteen years working with high school students; this was a new challenge for me, and I was ready for it.

The moment occurred during the first few weeks of the school year when I prepared a launch (a mini-lesson) focused on the proverb:

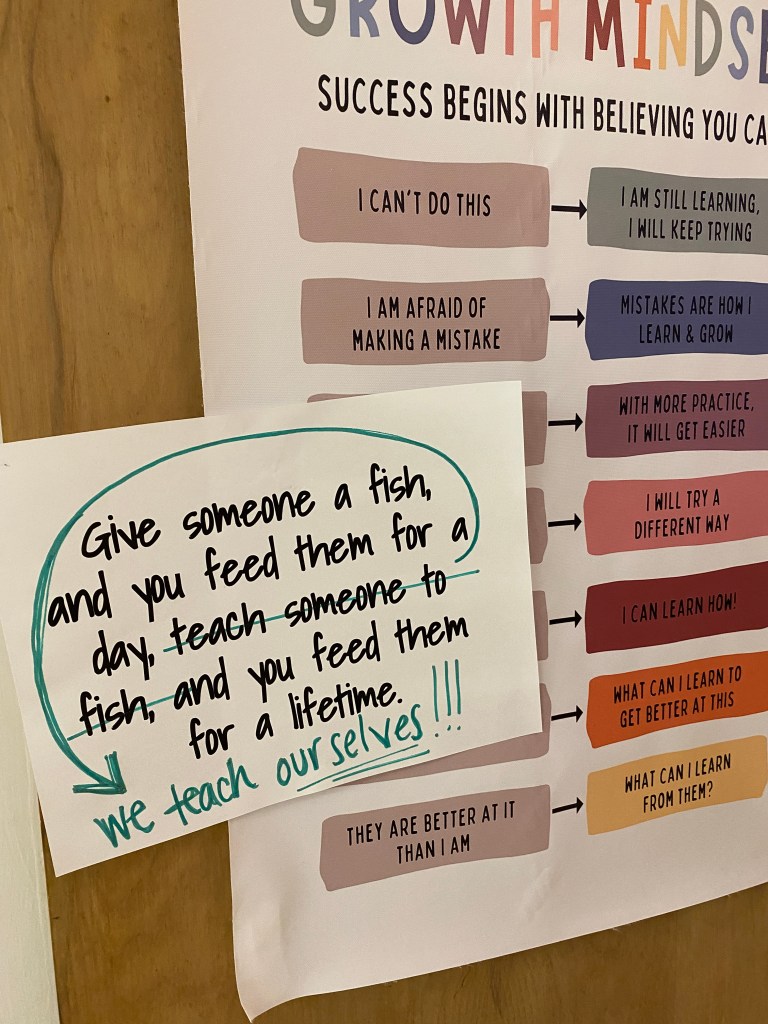

Give someone a fish and feed them for a day, teach someone to fish and you feed them for a lifetime.

The quote was displayed in a carefully chosen font on the large television screen and the learners were carefully arranged in a circle, ready for discussion. I was prepared and excited for my carefully planned discussion. I read the quote, shared the first socratic question, and what happened next was not what I had planned. The learners read the widely-accepted, well-known adage and tore it apart with one single comment:

Ms. Elizabeth, no one teaches us how to fish. We teach ourselves. This is The Village School, remember?

Talk about a mic drop moment. The lesson I had so carefully prepared for no longer applied. I remember thinking to myself:

Who are these kids and what is happening?

Are they really pushing back on an ancient proverb?

Who do they think they are and how can I be more like them?

I wasn’t sure if I was annoyed, impressed, or both. I’d like to say this was the first and last time the learners at The Village School found a loophole I didn’t see coming and took me on a journey I never anticipated, but this moment proved to be the first of many.

This particular failed discussion of fish was buried in my memory until a few weeks ago when I was observing one of our 8th graders give their final presentation as a TVS learner. She was asked what one of her most memorable moments was and she looked straight at me and said: That discussion about fish. That was a good one.

It took me a few minutes to retrieve the memory, and once found, the experience all came flooding back. Impressed by the fact that this three-years-ago conversation had stuck with her I realized its own significance to me and how so many of the discussions and experiences I have had over the past three years could be related back to the lesson this early conversation held: At TVS we teach ourselves to fish.

I’m not even sure which lesson gleaned here is the most important.

Is it that young people are just as or more wise than ancient wisdom?

Is it that young people are more capable of new analysis where adults see fixed understanding?

Is it that young people are adept critical thinkers when given a chance to think for themselves?

Or, is it that we actually have no idea what experiences might stay with a young person as a core memory that contributes to their understanding of themselves and their place in the world?

This particular learner referenced the fish discussion with a sense of pride. What was a moment of failure for me, was a source of empowerment for her, as she learned the power of questioning – or as she put it: I really love finding a loophole, and I’m good at it.

I think what she really found is the power in her own voice, and isn’t that what we all want for all our children?

Before this moment during her presentation, I had been sitting quietly and strategically in the corner of the room, trying my best to be a fly on the wall and simply take in the scene. I anticipate these end of year presentations with equal parts dread and joy. They are modeled after a Portfolio Defense, however at TVS the title “Character Defense” would be more accurate. We call them “Learning to Live Together” presentations, as learners must provide evidence of their growth in the character traits represented on our school’s Profile of a Learner. While other schools mark the end of the year with a summative test, we mark it with a celebration of character and growth.

These presentations often hold emotional moments between young people and the people who care about and spend the most time with them: their teachers and parents. I cherish the opportunity to observe the connection between these groups and the bittersweet reminder of the fleeting nature of childhood and the power of the TVS agentic learning model. As an observer I watch the dynamic between the learner and her audience.

I watched her mother’s face as she spoke about her growth in respect and accountability.

I watched her guide’s faces as she spoke about her ability to collaborate with her peers.

I felt my own face soften as she spoke about compassion towards others and herself.

I watched her own face when she said “I really just like myself. I like who I am.”

I watched her friend’s faces nodding in agreement, laughing quietly at a photograph in the presentation, or a reference to a joke only they understood.

I watched everyone in the room turn towards this young person with pride, a deep sense of respect, and reverence for their thoughts and ideas about their own learning experience. The magic of the Learning to Live Together presentation is that adults are asked to set aside their own judgements about how this young person had experienced school and life – and forced to lean in, listen and trust.

One of the TVS values is that we trust young people to learn from their own experiences, and these presentations are just one example of how we live out that value.

My favorite defense question to post to learners at the end of these presentations is to fill in the blank: I used to think…now I think about what they have learned about themselves as a result of their time at our school. Here are a few of their responses:

I used to think I didn’t have the power to change the world, but now I know that I do.

I used to think that I had to get everything perfect all the time and now I know that I don’t – even though I still want to.

I used to think that I wasn’t a leader, but now I think that I am.

I used to think I was the kind of person who didn’t care about school work, and now I think I am the kind of person who cares and I feel really good about it.

What a gift to learn such powerful lessons about yourself at such a young age. If one thing’s for sure, learners at TVS will leave knowing more about themselves than their peers – and sometimes their parents.

At the end of this school year, I was reminded that I used to think my role as a TVS guide was to teach young people how to fish – and now I think, my role is to cheer young people on as they teach themselves.