There’s a saying: there’s no such thing as bad weather–only inappropriate clothing. TVS learners know that. They just put on their rain coats, boots, snow pants or gloves, and run outside to play, no matter the weather.

Indoor recess? No thanks. TVS learners would rather make rain shelters, jump in muddy puddles, build obstacle courses, and just generally get as wet and messy as possible. In fact, if the water isn’t falling from the sky, the children take it from the hose. How else are they going to cool off on a 90-degree day?

Without a doubt, the rainy and windy days provide much of the hidden learning across studios. “Let’s make a shelter!” is all but assumed as soon as learners run out the door. They are making use of those problem-solving and teamwork skills we work on so hard on. It fell down? Great, how can we build it sturdier next time? That’s engineering!

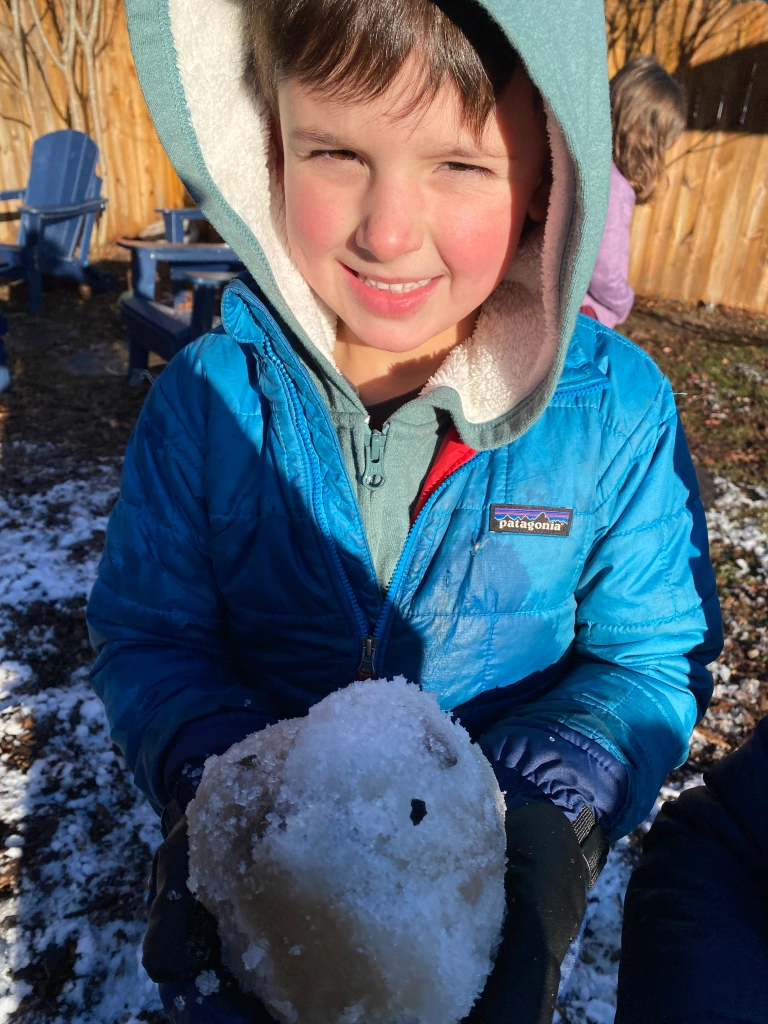

We treasure the occasional snow day. A silent and covered playground comes alive again as snow cones become Christmas trees we can decorate with nature treasures. Small snowmen turn into snow robots or minions to play with. The children run around to collect as much ice as they can from frozen puddles.

Even the wind can be its own toy. What can we use to make kites? What flutters or flaps in the breeze? What can we make to block the wind when we get cold?

At the end of it all, we get to come in, change into warm or dry clothes, and warm up with a good book.

That’s not to say we don’t love a gorgeous spring day. Not one of us would turn down a gentle breeze or pleasantly warm sun on a 74-degree afternoon. Some might call that a “perfect” day. But is it? If you’re talking about golden opportunities for learning, it’s debatable. Sure, precipitation and high or low temps may be inconvenient, but they are exciting, too. There’s something about having to work for your fun that makes it all the more rewarding. With the right prep and planning (check that forecast, everyone) any day can be a perfect day.

There’s a larger lesson here. We’re not just teaching learners that they needn’t wait for the ‘ideal conditions’ to play outside. We’re also teaching them not to wait for everything to be just right before they solve that problem, work as a team, or let the creativity flow. They can jump in to adapt and make the best of whatever comes their way.

We always say that the environment is the primary teacher. At TVS, that includes the outdoors. The imperfect and unpredictable outdoor environment teaches us to take initiative, show resilience, and stay optimistic in the face of difficulty. It teaches us that we can be OK no matter what. So bring on that wind, rain, and snow. We’ve got learning to do!